The day of the Resurrection or the resurrection or just any Sunday, depending. But I thought to comment on my previous post, “Eating Icons,” first published in a longer form in the oldest extant magazine in the country. I love history, so I like that about The North American Review.

The day of the Resurrection or the resurrection or just any Sunday, depending. But I thought to comment on my previous post, “Eating Icons,” first published in a longer form in the oldest extant magazine in the country. I love history, so I like that about The North American Review.

My true mentor in essay-writing is Vivian Gornick, a writer’s writer, fierce intellectual, and die-hard New Yorker. She teaches that good writing in the form of the personal essay must be alive on the page, bear the signature of its maker, so to speak, and always, always must implicate the self.

“Eating Icons” fails on all fronts.

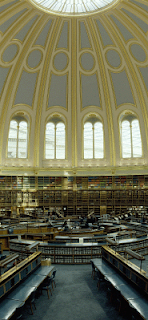

In 1994, I was living in London with my family, and daily making the trek from Hampstead on the Northern Line to Tottenham Court Station, then walking over to Bloomsbury, where the British Library was then, and sat under the dome (constructed 1857) and fell in love with the Reading Room as everyone had done before me, including Karl Marx. The seats are numbered and everyone knew where Marx had sat, toiling away on words that would throw a bomb into what had been known as the orderly march of history.

I was studying Slavic fairy tales. Then I was studying fairy tales in general, and then I was studying the origin of fire, and anthropology, and then 17th-century English cookery and history. That’s the way it is there, in the British Library. One thing leads to another.

Eggs show up in great numbers in fairy tales, and the story my friend had told me about her drawing of an egg was still lurking in my heart, and when I researched and wrote the piece I was able to pull in the folklore, and anthropology, and cookery, and everything else. Karl Marx was even in it indirectly, but was edited out for the blog posting. (It had to do with Fabergé eggs turning anyone into a Bolshevik.)

Right before I began writing the piece, my father killed himself. I returned to Phoenix, where we had been living before the move to London, in time to be with him as he died, and then I returned to London and took up eggs.

Eggs real and in the imagination kept me going through those months after. It was the best I could do. I didn’t want to talk about anything else, not on the page or in any other way.

I don’t believe in explaining things. Works of the imagination are, or should be, sufficient unto themselves. But as William Mulholland said when the stolen water from the Eastern Sierra came into Los Angeles: Here it is, take it — and I will add, only if you wish.